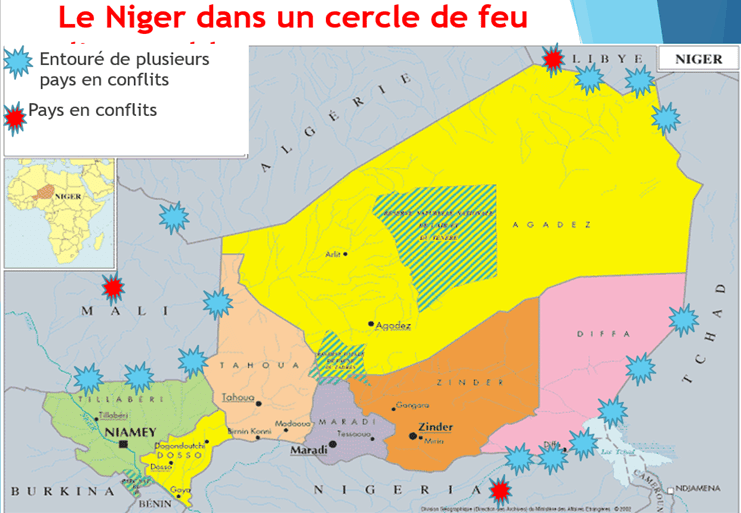

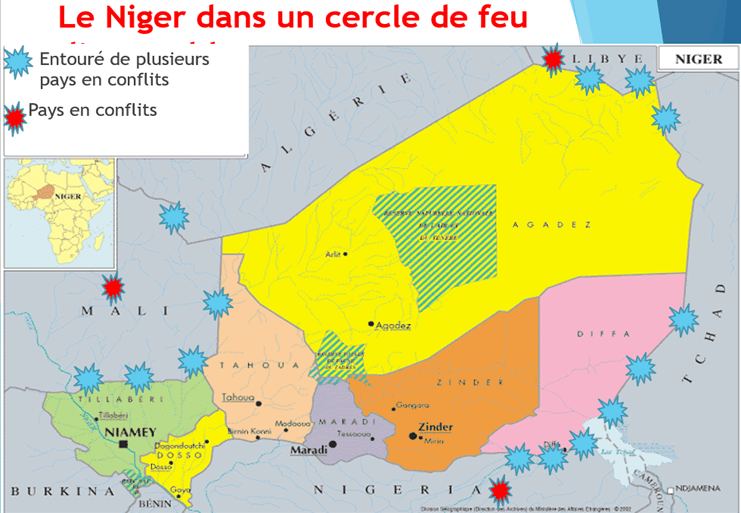

For almost a decade the Sahel has been fighting terrorism. This phenomenon, which was initially located mainly in Mali, has gradually spread to the rest of the region, affecting countries such as Niger, Burkina Faso, and Chad. Today, terrorism is present in the countries of the Gulf of Guinea such as Benin, Togo, Ghana and even the Ivory Coast.

On the ground, the fight is waged on several fronts: On the military front, on the judicial front, through development actions, awareness raising missions etc.

At the judicial level, the treatment provided by traditional actors such as investigators, prosecutors and judges grouped together within the criminal chain has revealed a major shortcoming which is at the origin of a situation of exacerbation of frustrations, violent extremism, and radicalisation, which constitute a ferment of recruitment for terrorist groups [1].

This gap? It is the gap that has been created and is widening every day between 3 key actors in this fight. On the one hand, the judicial system, which operates on the basis of rules of evidence regularly collected, reported and discussed in a fair trial; on the other hand, the army in the front line, which is used to fighting independence movements, is trying to contain this new phenomenon which appears to be a hydra; and, finally, the civilian population, for whom this fight is supposed to be conducted and who find themselves caught between two fires: On the one hand, the terrorist groups who try to win their hearts and minds by resorting to threats, assassinations and kidnappings, and on the other hand, the defence and security forces who consider these civilian populations as accomplices of the terrorists and treat them as such.

In Niger, this situation has led to mass arrests and detentions in deplorable conditions of people suspected of belonging to terrorist groups. However, the first hearings of the specialised court [2], which began in earnest in March 2017, revealed a very low rate of convictions. Indeed, only 10 per cent of the defendants were convicted and sentenced for terrorism-related offences. The other 90 per cent were released after several months or even years in detention. The judicial fight against terrorism then became mired in contradictions and inextricable reproaches. The misunderstood judicial system regularly received stone-throwing on the one hand from a population disappointed with its excessive delays and its groping, and on the other from the army, tempted to sink into the practices of summary executions that it observed elsewhere, in the face of a judicial system that it considered to be failing and even complacent.

To prevent the fight from getting bogged down, the judicial system designed and implemented a form for use by the army at each arrest, which constituted a first level of analysis of the facts. This form provides information on the author of the arrest, the person involved, the circumstances of the arrest, the objects found on the person, etc. [3]

Even if it is true that this sheet did not resolve all the difficulties raised, it had the advantage of allowing, for the first time, the investigators and the army, actors who have always observed each other from a distance, to finally be able to communicate on a technical, operational and precise basis.

The first positive impacts recorded have convinced us of the need to continue this dialogue through open and quasi-regular meetings between the judicial system, the army and by adding the civilian population, with the intermediation of the High Authority for Peacebuilding (HACP) [4], whose role is to strengthen peace and social cohesion. The first meetings showed how wide the gap was, particularly between the judiciary and the army, the latter not understanding the relevance of the latter’s involvement in the fight against terrorism. The recurrence of these meetings and, above all, the commitment shown by the authorities through the HACP gradually helped to ease the atmosphere, to restore serenity and to promote discussions on the substance. These meetings have become real frameworks for exchanges and above all for training where all subjects are tackled, including these essential themes for a good administration of justice:

- respect for the basic rules for gathering evidence

- respect for the rights of suspects and the rule of law,

- the necessary but measured involvement of local populations, in particular traditional chiefs and opinion leaders,

- Better coordination between specialized services and the primary actors who are local.

These meetings have undoubtedly led to the first drastic reductions in the number of people arrested and detained for belonging to terrorist movements. At the same time, the better prepared judicial procedures gradually increased the rate of convictions from 10% to nearly 65% in a very short time.

Obviously, all these efforts have made it possible to deal with conjectural situations. It is therefore up to the Nigerien justice system, to be more efficient and, taking advantage of the existence of this relaxed framework of exchanges, to move towards proactive investigations for effective prosecutions. That is one of the pillars of the training provided for the past two years to law practitioners by the Academic Unit of the International Institute for Justice and the Rule of Law (IIJ), an institution inspired by the Global Counter-Terrorism Forum.

Samna Cheibou, Resident Fellow, Academic Unit, April 2022.

Keywords: Army, civil society, Niger, Rabat Memorandum.

Download the full article here.

Télécharger l’article en français.

[1] In March 2017, Niamey’s prisons totalled nearly 1,700 people suspected of complicity with terrorist groups Source. Office of the Public Prosecutor

[2] ord. N°2011-12 of 27 January 2011JOSP n° 03 of 11 March 2011 see THE FIGHT AGAINST TERRORISM IN NIGER. LES APPROCHES JURIDIQUES by Zeinabou Abdou Hassane https://scienceetbiencommun.pressbooks.pub/droitniger/chapter/chapter-1/#:~:text=Depuis%20la%20Loi%20n%C2%B0,de%20r%C3%A9pression%20d’actes%20terroristes.

[3] ”When the dust settles, justice in the face of terrorism in the Sahel, Junko Nozawa and Melissa Lefas, October 2018 editor, Global center on cooperative Security https://www.globalcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/GC-2018-Oct-Dust-Settles-Judicial-Terrorism-Sahel-FRA.pdf See the article titled THE COORDINATION BETWEEN MILITARY ACTION AND JUDICIAL ACTION article by Mr Hassane Djibo magistrate of exceptional rank page 25 and following.

[4] Institution under the Presidency of the Republic, created by Decree No. 2011/217/PRN of 26 July 2011 to replace the High Commission for the Restoration of Peace (HCRP) created in 1994 during the successive rebellions that the country has experienced.